The beginning holds the key

“The details are not the details. They make the design” (Charles Eames)

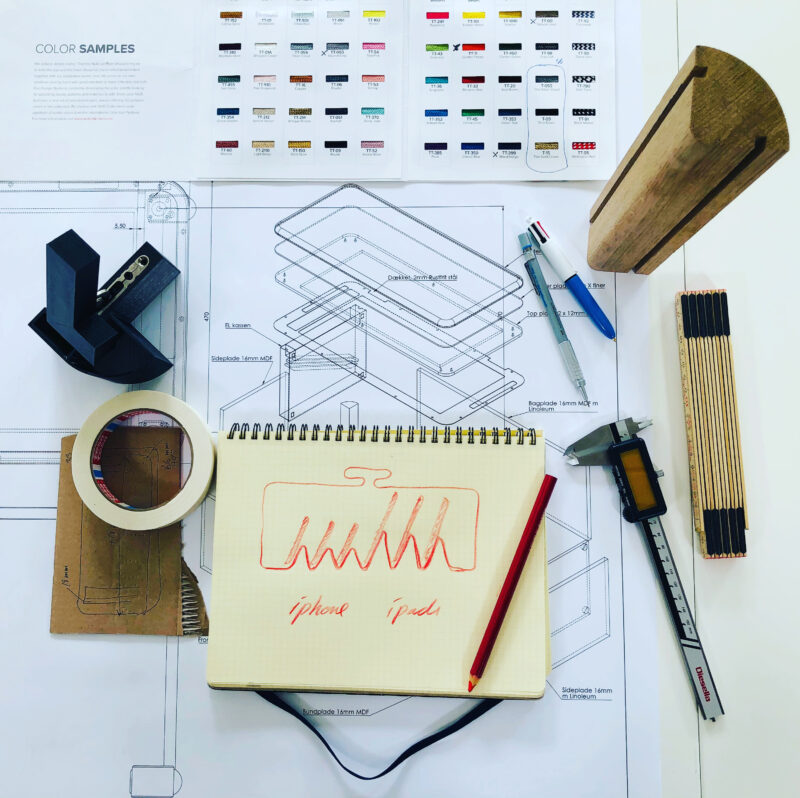

The key to designing a product that lasts lies in the very beginning of a project. The quality of the final product is determined by how thorough you’ve been in this initial phase; how well you’ve analysed the problem that the object is meant to solve; how far you’ve explored what the selected material allows for; how far you’ve tested whether the vision actually works in practice.

It can be compared to building a house. The foundation has to be secure and solid for the house to be safe. From an architectural perspective, the foundation also defines what’s possible in terms of the building’s final expression.

Designing furniture follows the same rule. The research phase determines all the following decisions you’re able to make in process. I often find that if the analysis has been solid enough, the product almost designs itself.

And yes, this phase takes time. And it involves a fair amount of painful ‘killing your darlings’ and frustrating fresh starts. But none of that is wasted. In fact, it’s the key to creating anything that lasts.

Great lessons come from big mistakes

The very first chair I got in production was called ALFA. I was really happy with it – and so was Botium, the manufacturer. We thought it looked really cool. It had a strong defined frame; an elegant, geometrical expression with sharp edges; and light and shadow balanced beautifully on its seat and backrest. We really believed this would be a winner.

There were just a few, shall we say minor problems. ALFA was not very comfortable to sit on, at least not for a longer period of time. It wasn’t stackable either, so you couldn’t really store it. And because of its sharp edges, it was fairly useless in high-usage areas such as canteens or conference rooms – simply because the edges would get damaged really quickly, and make the chair look battered and worn within no time.

The combination of these facts kind of explained why ALFA didn’t sell.*

At the time, this was obviously quite a slap in the face. Or rather a wake-up call. One I was glad to get early on, because it taught me at least two really important lessons that I’ve lived by ever since.

First, that testing is everything. It’s only when the object – a chair, a table, a lamp, whatever – is put to use in its proper environment that you really know whether your vision works.

Second, aesthetics should always be second to functionality. A chair might be beautiful – which I still think ALFA is. But if it doesn’t fulfill its purpose – which in the case of a chair is to support and provide comfort for the body when seated – then what’s the point? Or rather, then it’s no longer a functional object but a decorative one.

Given the huge impact that the production objects have on our planet – not to mention the efforts involved in their decomposition – I believe we, as designers, have the responsibility to ask ourselves: Do we really need to bring more objects into the world if they are not really relevant, or don’t fulfil their purpose properly?

* The CEO of Botium, Peter Stærk loved the ALFA chair, but he also saw the humouristic side of its legacy. He used to say that he put 400 copies in production and only two where sold: one to me and one to my mum! This is not entirely true, though. The chair proved to be particularly suited for spaces such as churches and chapels. So eventually, two Danish churches and a hospital chapel bought a slightly adjusted version of ALFA, which had better seating comfort.

UV BENCH